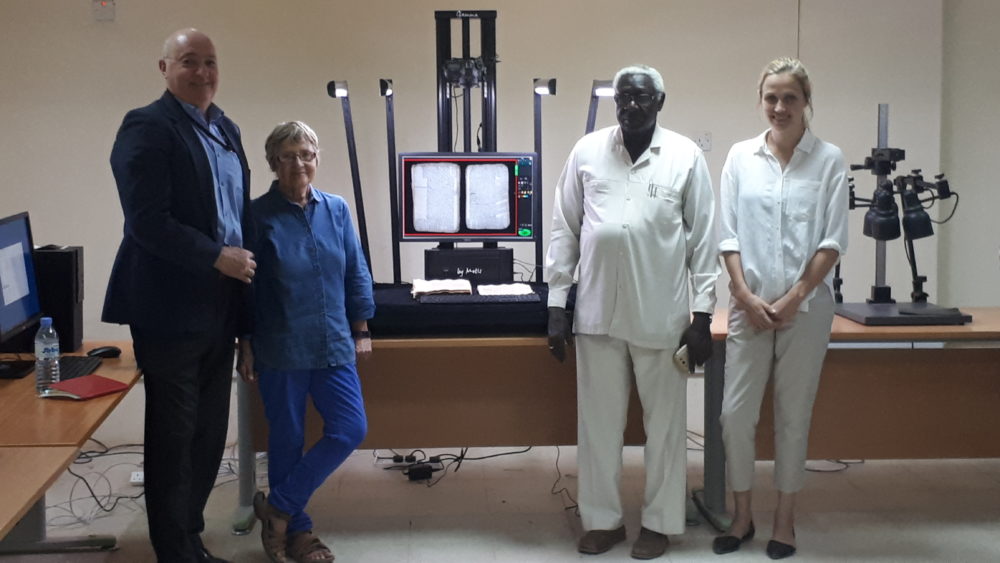

In July 2018 we were asked to supply digitisation equipment and staff training at The National Record office of Sudan and The University of Khartoum. Installation and training was provided by our Lead Engineer – Simon Brown and General Manager – Chris Elwell who installed Metis Gamma’s, camera copystations, A3 flatbeds, a wide format Rowe, networks and NAS devices. Chris and Simon spent a week in Sudan, visiting these archives to train the local staff on digitisation methods and how to use the equipment that was installed. This two-year project aims to conserve and digitise a range of written and photographic material held in archives in Sudan. While Sudan’s archaeological heritage is well-known through the many local and foreign teams that have been working in the country for more than 100 years, its non-archaeological culture is less known and understood outside the country, and much of this is in danger of deterioration and loss. Much of Sudan’s intangible tribal culture is not recorded or is recorded in obsolete formats or on rapidly decaying media, and ancient practices are being lost to younger members of society, with their reliance on smartphones and social media. But Sudanese people are justly proud of their culture and are passionate about its survival.

A group of institutions led by the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College, including the University of Liverpool, the Sudan National Records Office, Africa City of Technology and the Sudanese Association for Archiving Knowledge, got together to apply for funds to digitise cultural materials and to train staff in the archives and museums in Sudan in conservation, digitisation and asset management. Sudan Memory was the resulting project. The overriding aim of Sudan Memory is the promotion of the culture of Sudan to its own people and to the wider world. Alongside this is preservation and conservation, skill development, education, the preservation of disappearing cultures, and of personal and family memories.

The artefacts that represent the many cultures of Sudan include film, video and audio tapes, manuscripts, photographs, art works, and documents in archives throughout the country. The extent and scope of these is vast, and many are in a poor state, disintegrating, not well catalogued or curated, and in need of some kind of preservation. To give some examples, Sudan has one of the largest film archives in the whole of Africa, the Sudan Film Archive, containing, news reels, reportages and some documentaries based at the Sudan Radio and TV Corporation (SRTC). It has content going back to the 1940s and 50s, with around 13,000 film rolls, mostly 16mm and 35mm. These are of crucial importance as they record many different occasions and events in Sudanese public and private life: the first meeting of the Sudanese parliament in the run-up to independence; the independence ceremony; Queen Elizabeth visiting Sudan in 1965, regional dances and music; They are in a very poor state, and scanning is the only realistic option for saving the content. SRTC also has a large archive of radio and video tapes, some of which have been digitised, many more of which need conservation and copying.

Photograph of Halfa Reach (1920s), National Records Office

The National Records Office works under the auspices of the Council of Ministers and receives government documentation as hard copy. They claim to have items that go back as far as 1504, and it holds around 30 million documents. Of particular interest to the project are 40,000-50,000 letters from the Mahadia revolution/uprising at the end of the nineteenth century. The Ministry of Culture has a photo archive of millions of negatives and prints from the beginning of the twentieth century until the 1960s, covering a vast range of topics. The National Commission on Antiquities and Museums also has an archive of many thousands of slides, photographs, and large format maps and plans of archaeological sites.

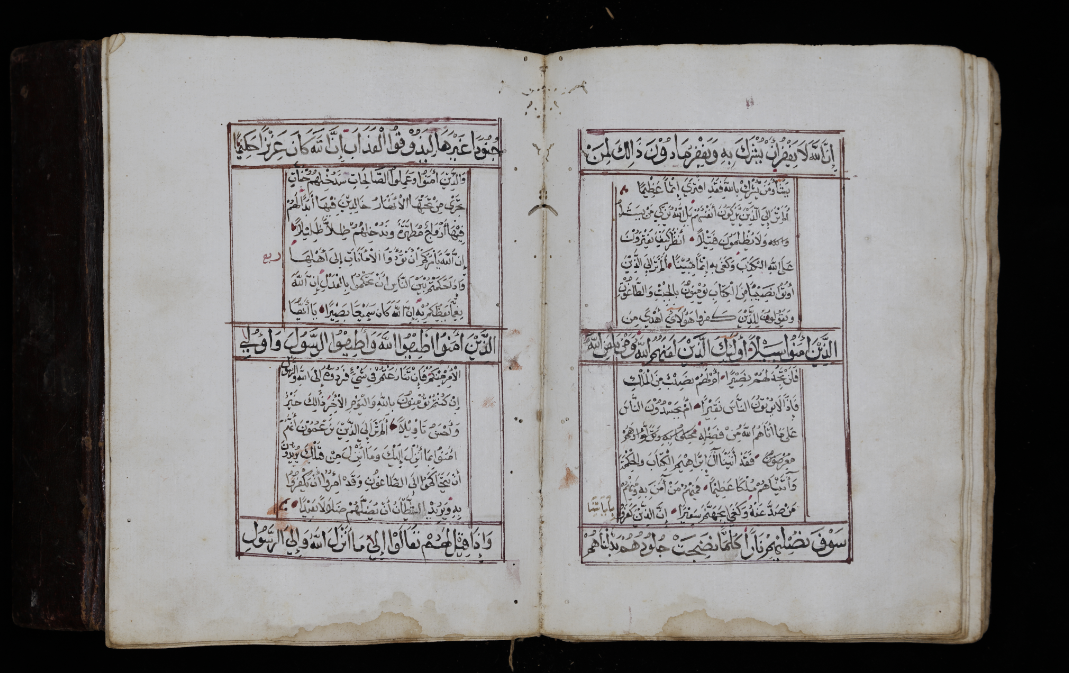

Islamic manuscript, University of Khartoum

The University of Khartoum is a major repository of important cultural records. The Sudan Library, part of the main university library, has the most important collection of books and manuscripts in the country, dating back around 800 years, and it functioned as the National Library until relatively recently. It has manuscripts that go back to the birth of Islam, as well as more modern materials: newspapers, magazines, printed books, maps. It is also rich in content concerning the period of British rule in Sudan. The Departments of Archaeology and of Engineering have maps, plans and manuscripts, and the Natural History Museum has a unique collection of the flora and fauna of Sudan which is being photographed for Sudan Memory. Outside Khartoum, other educational institutions hold significant content.

Content is also held in personal collections and in small museums and archives. The largest private photo studio in Sudan, the Al Rashid Studio in Atbara, has 4 million negatives dating back to the 1940s of public, private and family events, as well as of local industries: Atbara is the centre of the railway industry and has a railway museum. Collections of individual photographers have also been offered to us, such as those of the archaeologist Pavel Wolf who has been photographing the people and landscapes of Sudan for many years. There are also many small museums in towns and villages that hold content of value and interest to local communities, and families have collections that they are keen to preserve.

Women’s Museum Darfur, photograph by Kate Ashley

One personal local collection is the Women’s Museum in Nyala in Darfur, and a private collector in Omdurman has set up a museum-like display in his home, with many examples of aging technology (radios, televisions) as well as magazines, newspapers and photographs.

Why digitisation?

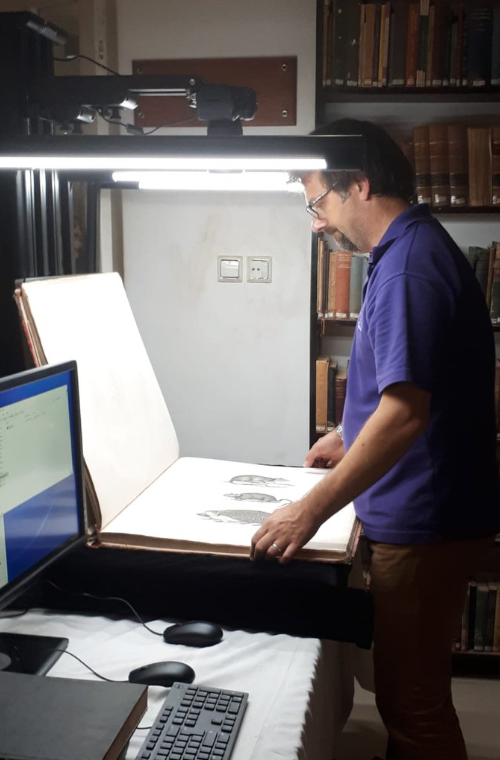

In an ideal world, with substantial funding, the first task of a project to help archive and conserve historical documents in Sudanese archives would be the conservation and protection of the analogue artefacts. But it was clear from our first experiences in Sudan that this is far beyond the scope of a short project, and the best we can aim for with the resources available to us is training and the raising of awareness of the staff in archives in the appropriate handling of their contents. We started from a perspective of first-world assumptions about standards and methods, and as a medievalist and a manuscript specialist, I come from a world of forensic accuracy in digitisation: we want to see every scratch, gloss, every hair follicle on the parchment. Damaged and poorly conserved modern papers and film in a country like Sudan are a different proposition, and you have to work out not what is the counsel of perfection, but what is good enough? What is better than doing nothing? Happily, digitisation has moved a long way since the early 1990s, when I began working in this area, and it is possible to get good enough results with lower cost equipment. We are working with a huge range of types of capture equipment: from the high end forensic quality scanners we are using at the University of Khartoum and the National Records Office, to mobile phones and low end scanners costing less than 100 dollars that we will be sending to small villages to capture family documents and photographs.

Chris Elwell from Genus training staff on the Metis Gamma at The National Record Office

As ever in digitisation projects, while scanning can be a challenge, metadata is an even bigger one. Working with large institutions like the National Records Office and the National Museum, we were assured that they had catalogues and that we would have access to the records. But the catalogues are many and varied, and much material is not catalogued to the degree we need or in the best way for online retrieval: they have gaps and many documents are misplaced, e.g. put in the wrong box; some cataloguing is only on box level, some items are not catalogued at all. Scanning can be done at the click of a button (once the equipment is set up). Metadata takes much longer. We have therefore had to set up our own relatively simple cataloguing system, and to train the Sudanese staff in this. When the images are made available we hope to enhance the descriptions by crowdsourcing and asking users to add to the metadata.

What we have achieved

Despite the many issues we have faced, there have been some notable successes. In the Sudan Film Archive, a local company, Dal Group, built a new facility for the storage of the deteriorating films. The University of Bergen, with funds from the Norwegian Embassy in Khartoum, installed film scanning equipment in the Archive and trained around 15 staff in its use. The funding for the staff ran out in June 2018, and so Sudan Memory stepped in to continue the support, and we incorporated the project (and the project manager) into Sudan Memory. Of the 13,000 existent films, 1000 have been cleaned, repaired and scanned.

The National Commission on Antiquities and Museums has also been running scanning projects in an archive which contains slides, photographs, and large format maps and plans of archaeological sites. Originally equipped by the German Archaeological Service, we have contributed two high power professional scanners for maps and photos, as well as other photographic equipment.

University of Khartoum

At the National Records Office, staff have been scanning manuscripts, newspapers, magazines and photographs. There are also many photographs of the large engineering projects undertaken by the British: dams, bridges, the railway, as well as what are clearly personal holiday pictures. The University of Khartoum team has scanned manuscripts, printed books and magazines, though at the time of writing, the University has been closed for several months because of the anti-government protests.

We have made good progress with personal collections: we have installed internet routers, scanners and computers in the House of Heritage in Abri—a town which has only had electricity for two years. Scanning has started on the Al Rashid collection, equipment and training have been given, and we are providing facilities for a mobile team of technicians to go into people’s homes to capture materials.

What next?

In the final six months of the project we will, as far as circumstances allow, continue scanning in the institutions that have already started, and we will also have an increased focus on private collections with magazines, photos and objects. We have also engaged a photographer to capture images of some of the historic architecture of Khartoum. Editing and correcting of the metadata and other texts are underway, and are proving to be challenging. Arabic grammar and spelling are extremely complex and can only be reliably checked by an expert, not by any mother tongue speaker. The Arabic then has to be translated into English and the English into Arabic.

Work has started on the portal and on plans for long-term preservation of the data, and we will be uploading images and metadata for testing very soon. We are commissioning short articles on a variety of topics to contextualise the scanned materials, and will make connections with other works and with international archives that hold content from Sudan: reunification of Sudanese materials in the digital space

After such significant investment in the project by so many stakeholders, not least the British Council who provided the funding, it is essential that it survives and thrives for the future. Currently we are in discussion with various organisations about the possibility of setting up a social enterprise to carry the work forward. This of course, to a large degree, will depend on what kind of Sudan will emerge from the present revolution.

Simon Brown and Chris Elwell of Genus delivering imaging equipment to the University of Khartoum with Marilyn Deegan of KCL

Acknowledgements

There are so many organisations that have contributed and continue to contribute to the project. First of all the British Council: the Cultural Protection Fund and British Council Sudan, Catriona Jackson and her team at the CPF, and Robin Davies and his team in Sudan in particular. The partners listed above and all the contributing institutions; ScanDataExperts, our main digitisation consultants; (Geoff Laycock and Peter Horsman); the companies Intranda GmbH (Steffen Hankiewicz and Jan Vonde) and Genus (Simon Brown and Chris Elwell) who supply software and hardware. The participants in the Western Sudan Community Museums Project, especially Michael and Helen Mallinson, and Kate Ashley. The administrative and financial staff at King’s College who deal with our complex technical and financial needs. Particular thanks go to the teams in Sudan carrying out the work on the ground, led by our wonderful project manager, Katharina von Schroeder.

By Marilyn Deegan, Department of Digital Humanities, Kings College London.

Comments are closed.